BRICKSTORM Is a Wake-Up Call: Stop What You're Doing and Protect Your DMZ

On December 4th, CISA, the NSA, and Canadian Centre for Cyber Security dropped a joint advisory that should have every IT and security leader pulling up their network diagrams.  The threat? BRICKSTORM, a sophisticated backdoor attributed to PRC state-sponsored actors that has been quietly living inside government and critical infrastructure networks for over a year. In one documented case, attackers maintained persistent access from April 2024 through at least September 2025. That's 393 days of undetected dwell time.

The threat? BRICKSTORM, a sophisticated backdoor attributed to PRC state-sponsored actors that has been quietly living inside government and critical infrastructure networks for over a year. In one documented case, attackers maintained persistent access from April 2024 through at least September 2025. That's 393 days of undetected dwell time.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: BRICKSTORM isn't special. It's today's headline. Tomorrow it will be something else, a different malware family, a different nation-state actor, a different CVE. The attack pattern, however, will be depressingly familiar. And that pattern is exactly what we need to talk about.

The Kill Chain We Keep Ignoring

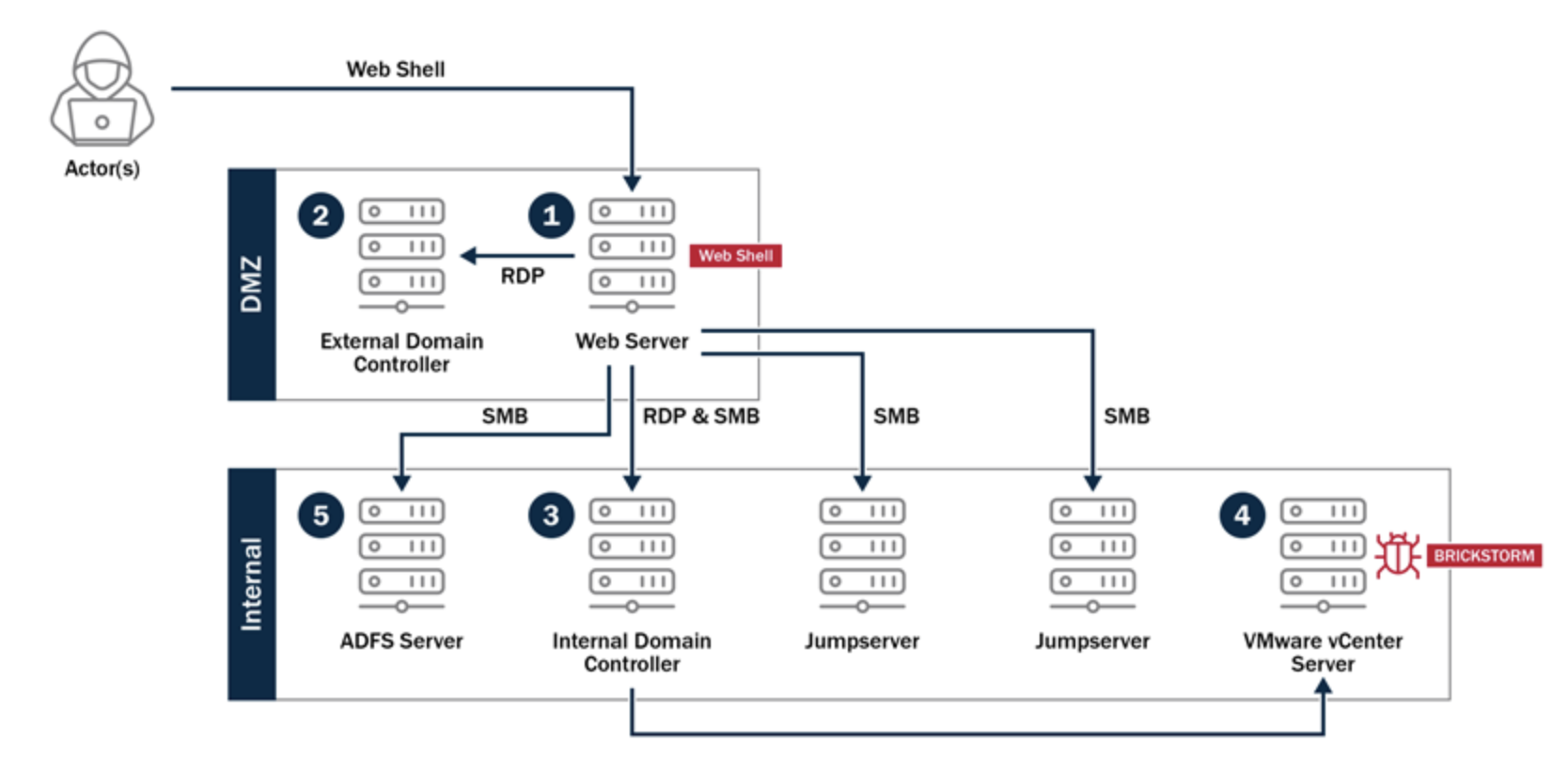

Look at how the CISA-documented intrusion actually unfolded. Attackers gained access to a web server sitting in the organization's DMZ. From that single foothold, they used RDP to pivot to a domain controller in the DMZ. Then, using a combination of RDP and SMB, they moved laterally to the internal domain controller. From there, SMB connections fanned out to jump servers and ultimately to the VMware vCenter server where BRICKSTORM was deployed. Along the way, they compromised an ADFS server and exfiltrated cryptographic keys.

Fig 1. How the BRICKSTORM attack was deployed.

Source: "BRICKSTORM Backdoor" diagram from CISA Malware Analysis Report AR25-338A (December 4, 2025).

The diagram of this attack is a masterclass in what happens when network segmentation exists only on paper. Every hop in that kill chain, every RDP session, every SMB connection, represents a door that was left wide open because "it's all internal" or "some other system needs access to do its job." Years of built-up firewall exceptions have made the defenses between the DMZ and the internal network a sieve.

Here's my plea to every security practitioner reading this: Please, stop what you're doing and ask yourself one question. If an attacker planted a web shell on your DMZ web server right now, how far could they get before hitting a wall?

If the answer makes you uncomfortable, you're not alone. But you need to act.

The DMZ Is Not a Castle Wall. It's the Front Door.

Somewhere along the way, we started treating the DMZ like it was protecting us. We put our web servers there, our edge applications, our externally-facing services, and we told ourselves that the firewalls would keep the bad actors out. We built elaborate rules and deployed threat detection to control traffic DMZ into the corporate network, but these couldn’t stop credentialed attacks - even if it doesn’t make sense for a web server to be logging in to a domain controller.

The result is an architecture where a compromised DMZ system becomes a launch pad for lateral movement. RDP ports are open because administrators need to manage servers. SMB is available because applications need to access file shares. Domain authentication is enabled because everything needs to join the domain. Each of these conveniences is also an attack pathway.

The BRICKSTORM campaign exploited exactly this pattern. The attackers didn't need a sophisticated zero-day chain to reach vCenter. They just needed credentials and open protocols. Once they had that web shell, the network was their oyster.

"We're Doing Zero Trust" Usually Means You're Not

I've lost count of how many times I've heard "we're implementing Zero Trust" followed by descriptions of projects that won't deliver results for 18 to 24 months. But there's an even more common problem: organizations that believe they've already achieved Zero Trust because they deployed a ZTNA solution.

Let's be clear about what ZTNA does and doesn't do. Zero Trust Network Access is designed to secure remote user access to applications. It replaces VPNs, it verifies user identity, and it grants access to specific resources rather than entire network segments. For that use case, it's excellent.

But ZTNA does absolutely nothing to protect a web server sitting in your DMZ.

That web server isn't a user. It doesn't authenticate through your identity provider. It doesn't connect through a ZTNA client. It's a workload, and when an attacker drops a web shell on it, they inherit whatever network access that server already has. Your ZTNA deployment won't even see the lateral movement happening because it's not in the path.

The BRICKSTORM attack is a perfect illustration. The threat actors moved from a DMZ web server to domain controllers, jump servers, ADFS, and vCenter using RDP and SMB. None of that traffic would ever touch a ZTNA solution. The organization could have had the most sophisticated remote access architecture in the world, and it wouldn't have slowed down this attack by a single second.

Zero Trust for workloads requires a different approach: identity-based controls applied at the server level that govern what processes can communicate with what resources. This is microsegmentation done right, not at the network layer where everything looks like an IP address, but at the application layer where you can enforce that a web server has no business initiating RDP connections.

What Would Have Stopped BRICKSTORM?

What Would Have Stopped BRICKSTORM?

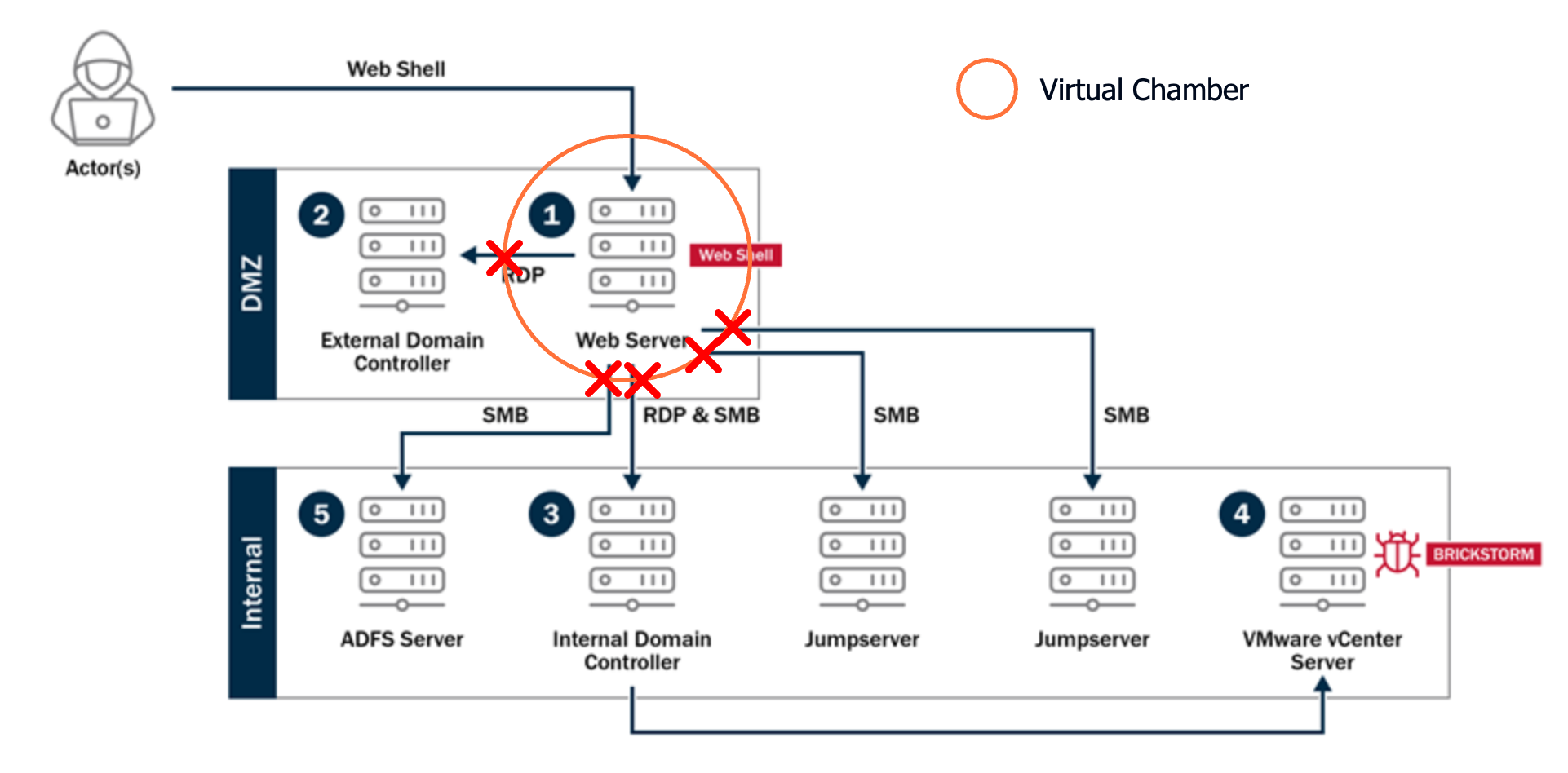

Let's be specific. In the documented attack, here's what Zero Trust controls on the DMZ web server would have prevented:

- The web shell would have been unable to initiate RDP connections to the domain controller. Even if the attackers had credentials, the connection would never have been allowed because the web application identity had no business using RDP.

- SMB connections to internal systems, the jump servers, the ADFS server, the vCenter host, would have been blocked at the source. A web server serving HTTP traffic shouldn’t have broad SMB access. If needed, the web server could still connect to ADFS - just using the appropriate services.

Every subsequent step in the kill chain depended on that initial lateral movement. Stop the first pivot, and you stop the entire campaign.

The same principle applies on the receiving end. Zero Trust controls on the internal domain controller, the vCenter server, or the ADFS server would have restricted inbound connections to authorized sources. A web server in the DMZ would never have been on that list.

Fig 2. Placing the web server in a Virtual Chamber would have given the organization the controls needed to identify and block all unauthorized accesses to the rest of the corporate network.

Tomorrow's Threat, Today's Defenses

BRICKSTORM was particularly insidious because it targeted VMware vCenter, the control plane for virtualization infrastructure that often receives less security scrutiny than endpoints or applications. But the attack didn't start at vCenter. It started at a web server in the DMZ and worked its way in through standard management protocols that were left exposed.

The next campaign will follow a similar pattern with different tools. It might be ransomware instead of espionage. It might target a different sector. The CVEs will be different, the malware will have a different name, and the threat intelligence reports will document different indicators of compromise. But the fundamental weakness being exploited, implicit trust and unrestricted lateral movement from DMZ systems, will be the same.

You have the ability to break this pattern today. Not by extending your ZTNA rollout, not by starting another 18-month project, but by making a decision to treat your DMZ assets as the high-risk systems they actually are and applying Zero Trust principles to constrain what they can do.

At Zentera, this is exactly what we help organizations accomplish: locking down lateral movement using identity-based controls that deploy without network changes. But regardless of which approach you take, the important thing is that you take action now.

BRICKSTORM spent 393 days inside a victim network. How long will the next threat spend inside yours?