Legacy Shadows: Illuminating Zero Trust Paths for Agencies in Brownfield Battles

How federal agencies and their contractors can achieve Zero Trust for OT without disrupting mission-critical operations

A control systems engineer is handed a mandate to achieve Target Level Zero Trust across an operational technology environment built decades before identity, encryption, or segmentation were design considerations. The PLCs cannot authenticate. The network cannot be re-architected. Downtime is measured in risk to mission, not inconvenience.

This is no longer a hypothetical.

With the release of the DoD CIO's Zero Trust for Operational Technology Activities and Outcomes guidance and the issuance of DTM 25-003, every DoD Component is now directed to achieve Target Level Zero Trust across Operational Technology (OT) and Industrial Control Systems (ICS). The guidance formalizes what many practitioners already knew: securing OT is no longer optional, and Zero Trust principles must extend beyond enterprise IT into the systems that control physical processes.

While the guidance originates from the Department of Defense, its implications extend well beyond it. Agencies across the federal landscape, including the Department of Energy, CISA, and civilian agencies operating critical infrastructure, face the same challenge of how to implement Zero Trust for legacy, brownfield OT environments without disrupting safety, availability, or mission execution.

The question is no longer why Zero Trust for OT is necessary.

Volt Typhoon's sustained presence in critical infrastructure networks settled that debate.

The real question is how.

How do agencies meet Zero Trust requirements when their environments include PLCs running protocols from the 1980s?

How do they implement microsegmentation, session authentication, and authorization controls in ICS and SCADA systems that were never designed to support them?

And how do contractors scale these implementations across dozens or hundreds of unique OT environments without creating brittle, one-off solutions?

The answer is not found in fighting brownfield reality.

It is found in adopting architectures designed for it.

What the DoD Got Right About Zero Trust for OT

The DoD's Zero Trust OT guidance is notable not for being aspirational, but for being grounded in operational reality.

Among its most important contributions:

Recognition of OT constraints. Long asset lifecycles, limited maintenance windows, and legacy protocols are treated as givens, not failures.

Layered abstraction. The distinction between the Operational Layer and Process Control Layer provides a useful mental model for risk management and control placement.

Allowance for alternative mitigating controls. The guidance explicitly acknowledges that many OT assets cannot support periodic authentication, certificates, or native identity, and that Zero Trust must still be achievable.

In short, the DoD is not asking agencies to modernize OT overnight.

It is asking them to achieve Zero Trust outcomes, even when traditional Zero Trust mechanisms are unavailable.

That distinction matters.

The Implementation Gap: Where Most OT Zero Trust Programs Will Struggle

The DoD defines 84 Target Activities spanning identity, segmentation, visibility, and policy enforcement. Individually, these activities are reasonable. Collectively, they describe a transformation that, if interpreted literally, could take years using traditional rip-and-replace approaches.

Years that adversaries will not grant.

This is the core tension facing agencies and contractors today:

Zero Trust for OT is required now, but OT environments were never designed to change quickly.

Attempting to force enterprise IT Zero Trust tooling directly into ICS and SCADA environments often results in fragile integrations, excessive customization, operational risk, and inconsistent enforcement across sites.

The result is not Zero Trust. It is complexity.

To succeed, agencies need an approach that:

- Works in brownfield OT environments

- Supports DoD Zero Trust OT activities

- Preserves availability, safety, and mission continuity

- Scales across diverse facilities and asset types

That requires a different architectural assumption.

Taken together, these challenges reveal a fundamental truth about Zero Trust for OT: success depends less on individual tools or controls than on whether the architecture accommodates legacy reality. This tension between modern Zero Trust requirements and decades-old operational environments defines what we refer to as the Brownfield Paradox.

How Can Agencies Achieve Zero Trust for Legacy OT?

Agencies do not need every OT asset to become identity-aware.

They need an architecture that can enforce Zero Trust on behalf of those assets.

This is where overlay-based Zero Trust architectures for OT become essential.

Rather than replacing networks or retrofitting legacy controllers, an overlay approach introduces a software-defined Zero Trust security fabric that:

- Enforces identity-based access to OT and ICS assets

- Enables microsegmentation for industrial control systems without network redesign

- Supports alternative mitigating controls aligned to NIST SP 800-207

- Applies consistent policy across IT, OT, and hybrid environments

In the sections that follow, we explore how this approach addresses the brownfield paradox, enables repeatable Zero Trust deployments for contractors, and translates federal guidance into operational capability without disrupting the systems that missions depend on.

The Brownfield Paradox: Constraints That Define the Solution

The Brownfield Paradox is simple: the environments most in need of Zero Trust protection are the least capable of implementing it natively.

The Brownfield Paradox is simple: the environments most in need of Zero Trust protection are the least capable of implementing it natively.

These challenges aren't unique to defense installations. Energy sector facilities operating under NERC CIP requirements face identical challenges. Water treatment plants, transportation systems, and federal building automation systems all share the same brownfield realities.

The implementation gap becomes clear when requirements are examined together rather than in isolation. Macrosegmentation and microsegmentation assumes network flexibility. NPE certificate management assumes devices that can hold certificates. Authorization controls assume systems capable of enforcing them.

For environments where these assumptions don't hold, the path forward requires architectures that can impose Zero Trust externally rather than expecting legacy assets to participate natively.

This is not a failure of policy. It is a mismatch between architectural assumptions and operational reality.

The Contractor's Dilemma: Diversity at Scale

For contractors supporting federal missions, whether large integrators or specialized OT security firms, the complexity multiplies across every engagement. One agency operates water treatment facilities with decades-old SCADA systems. Another manages manufacturing control systems where a single hour of downtime costs more than the annual security budget. A third maintains facility-related control systems across hundreds of geographically dispersed installations.

Each environment presents unique constraints: different legacy equipment, different industrial protocols, different operational criticality, different risk tolerances. Traditional approaches would require custom solutions for each, resulting in different tools, different integrations, different training, and different support structures. The result is a fractured capability that's difficult to scale, expensive to maintain, and impossible to standardize.

What agencies and their contractors need is an approach that creates institutional muscle memory. A repeatable methodology that works regardless of the specific brownfield challenges encountered. The same team that successfully implements Zero Trust at a power generation facility should be able to apply that expertise to a water treatment plant or manufacturing line without starting from scratch.

Programmable Pathways: The Overlay Approach to OT Zero Trust

The architectural innovation that makes this possible is the Zero Trust overlay, a software-defined security fabric that deploys on top of existing infrastructure rather than requiring its replacement. This approach directly addresses the guidance's emphasis on non-disruptive implementation and aligns with the fundamental principle that OT Zero Trust must maintain acceptable process control and safety performance.

Consider how this maps to foundational Zero Trust requirements:

Programmable Communication Pathways: Zero Trust architectures call for segmentation gateways and authentication decision points integrated into software-defined or alternative networking infrastructure. An overlay architecture delivers exactly this capability: programmable communications that can be instantiated, modified, and enforced through centralized policy without touching the underlying network infrastructure.

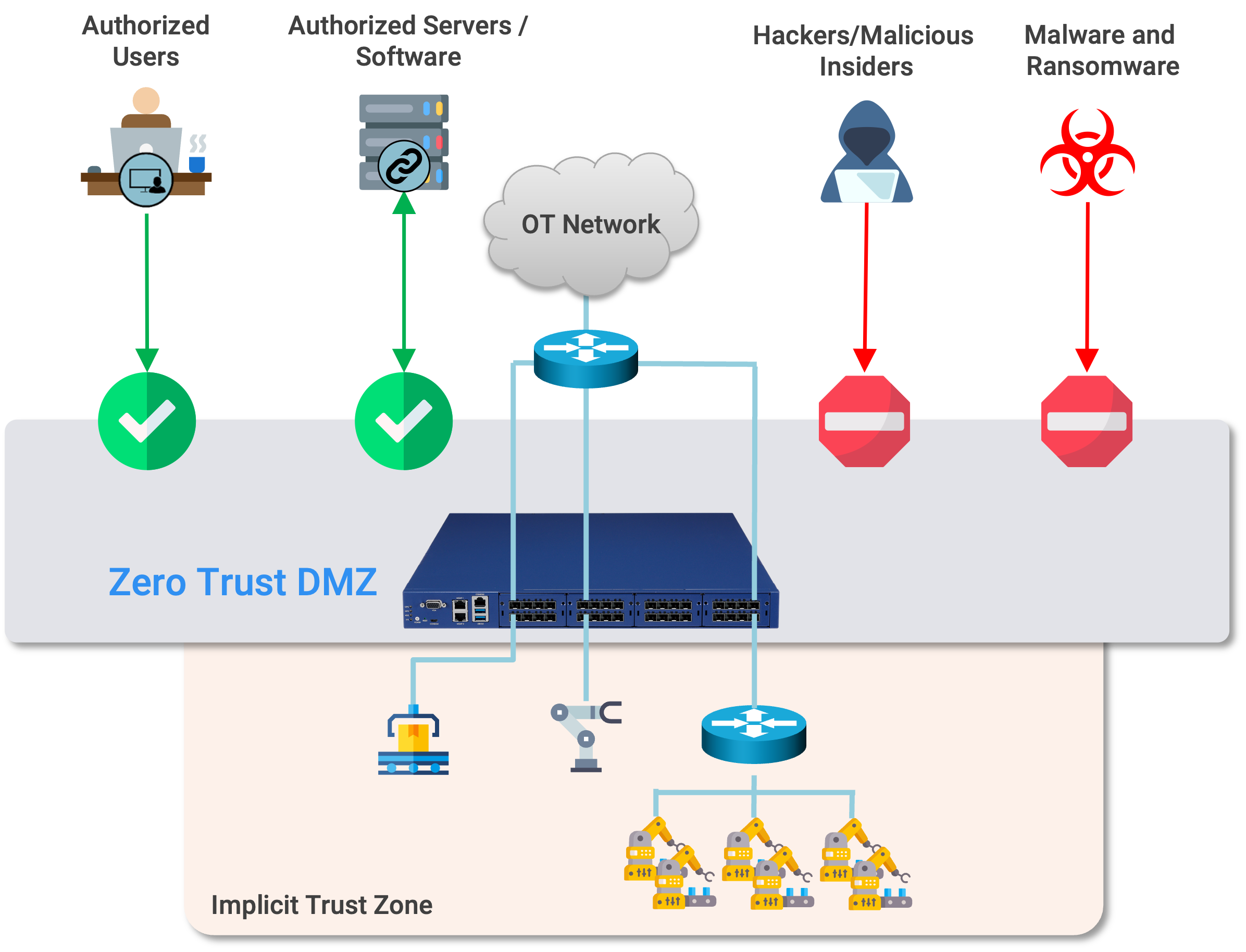

Session Authentication and Authorization: Modern Zero Trust requires authentication at the start of every session across both Operational and Process Control levels. The overlay achieves this for legacy systems by inverting the problem: rather than asking an identity-less PLC to authenticate requestors, the platform strongly verifies every inbound connection using available identity factors (user, device, and software) before allowing traffic to reach the protected asset. The asset itself is treated as trusted within its Virtual Chambers; everything approaching it must prove who and what it is.

Microsegmentation: Comprehensive Zero Trust demands segmentation across all information flow, including logical network zones with role-based, attribute-based, and condition-based access controls. Virtual segmentation constructs allow these boundaries to be created logically rather than physically, grouping assets by security requirements rather than by their position in the network topology.

Flexible Enforcement Across the Asset Spectrum

The power of an overlay architecture lies in its ability to apply consistent Zero Trust policy across assets with vastly different capabilities. A modern Windows server in the Operational layer, a Linux-based historian, a decades-old PLC in the Process Control layer, and a remote engineer's laptop can all participate in the same security fabric, governed by the same policy model, managed through the same orchestration interface.

This consistency comes from matching enforcement mechanisms to asset capabilities:

Agent-based protection for systems that can run software covers the broadest range of the OT environment. Modern servers, virtualized instances, cloud workloads, and even legacy operating systems like Windows XP or older Linux distributions can host lightweight agents that tie endpoint identity, application flows, and network access to centralized policy decisions. These agents enforce microsegmentation and access policies directly on the host, avoiding network changes.

Appliance-based protection extends Zero Trust to devices that cannot run agents, the legacy PLCs, RTUs, and HMIs that form the backbone of critical infrastructure. Inline security appliances positioned as a "bump in the wire" enforce identity-based access controls and microsegmentation policies without requiring any modification to the devices or the network. Hardware bypass ensures availability for operational resilience. Form factors range from rugged fanless DIN-rail units to high-density 1U rack-mount appliances for the wiring closet, matching the solution to the operational context.

Centralized orchestration unifies both enforcement approaches under a single policy framework. Security policies defined once apply consistently whether enforced by an agent on a modern server or an appliance protecting a legacy controller. This eliminates the policy fragmentation that plagues environments with multiple point solutions and enables the institutional muscle memory that makes Zero Trust scalable.

For a 20-year-old PLC controlling a critical process, appliance-based enforcement means:

- Identity enforcement without agent installation: Users must authenticate through the security fabric before any packets reach the device

- Protocol-agnostic protection: Industrial protocols are secured at the session layer without requiring deep packet inspection that could introduce latency or break operations

- Fail-open design: Hardware bypass ensures that security appliance failure doesn't become a single point of failure for operational availability

- Incremental deployment: Protection can be extended to additional assets during scheduled maintenance windows without requiring wholesale network changes

This flexibility directly addresses requirements to block unauthorized remote and local access while respecting the reality that many OT devices don't support periodic authentication and may require alternative mitigating controls.

NIST SP 800-207 Alignment: Building on Proven Architecture

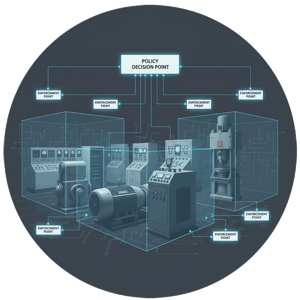

Federal Zero Trust guidance across agencies builds upon the principles established in NIST SP 800-207, and any implementation approach should maintain fidelity to that architectural foundation. The key components map directly:

- Policy Decision Point (PDP): Centralized orchestration that continuously evaluates trust based on user identity, device posture, application context, and environmental conditions

- Policy Enforcement Point (PEP): Distributed enforcement through agents on capable systems and inline appliances for legacy equipment

- Implicit Trust Zone Elimination: Enforcement at the endpoint level rather than at network boundaries, ensuring no hidden trust zones exist between security checkpoints

This architecture supports interoperability between component-level credentialing services and enterprise-wide identity authorities while ensuring risks involving communications between Process Control and Operational IT environments are properly mitigated.

Creating Institutional Muscle Memory

For agencies and contractors alike, the greatest value of a standardized overlay approach isn't just technical. It's organizational. When the same architectural patterns, the same policy model, and the same orchestration tools apply across diverse environments, expertise compounds rather than fragments.

The engineering team that learns to deploy Virtual Chambers at one installation brings that experience to the next engagement. The policies developed for one industrial protocol inform policies for others. The integration patterns established with one identity infrastructure provide templates for the next. Whether the enforcement point is an agent on a modern server or an appliance protecting legacy equipment, the concepts remain consistent.

This institutional muscle memory is what transforms Zero Trust implementation from a project into a capability. A repeatable, scalable competency that can be deployed across the federal enterprise efficiently and effectively.

The Path Forward

Federal Zero Trust guidance for OT represents a significant step forward in protecting the control systems that underpin national security and critical services. Whether originating from the DoD, DoE, or other agencies, these frameworks provide clear objectives. What organizations need now is a clear path to achieving them.

That path runs through brownfield-native architecture. Through overlay approaches that work with existing infrastructure rather than against it. Through flexible enforcement that matches protection mechanisms to asset capabilities. Through programmable policies that can adapt to diverse operational requirements.

The shadows of legacy systems will loom large for years to come. But with the right architectural approach, they don't have to remain in darkness.

Ready to explore how Zero Trust can protect your OT environment without disrupting operations? Contact Zentera to learn how our CoIP Platform can help you achieve Zero Trust compliance across any brownfield environment.