Why New OT Threat Groups Are Forcing a Reckoning With OT Network Security

Three new adversary groups began targeting industrial control systems in 2025. That’s the headline finding from Dragos’ 9th Annual Year in Review OT/ICS Cybersecurity Report - and the details behind it should concern anyone responsible for securing manufacturing plants, utilities, or critical infrastructure.

The three newly tracked groups - Sylvanite, Azurite, and Pyroxene - aren’t operating the same way. Each represents a distinct threat model, and together they illustrate how the industrial threat landscape is diversifying in ways that traditional OT network security architectures were never designed to handle.

Three Groups. Three Attack Models. One Common Target: Your OT Network.

Sylvanite functions as what Dragos calls a “rapid exploitation broker,” enabling another group, Voltzite - known for long-term persistence inside the U.S. electric grid - to access critical infrastructure targets. Sylvanite exploited Ivanti VPN vulnerabilities within 48 hours of their public disclosure and has installed persistent web shells on F5 appliances across electric power, oil and gas, water, and manufacturing sectors in North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific.

Sylvanite functions as what Dragos calls a “rapid exploitation broker,” enabling another group, Voltzite - known for long-term persistence inside the U.S. electric grid - to access critical infrastructure targets. Sylvanite exploited Ivanti VPN vulnerabilities within 48 hours of their public disclosure and has installed persistent web shells on F5 appliances across electric power, oil and gas, water, and manufacturing sectors in North America, Europe, and Asia-Pacific.

Azurite, linked with moderate confidence to China-nexus threat actors including Flax Typhoon and UNC5923, has exfiltrated OT network diagrams, alarm data, PLC configurations, and HMI data from manufacturing, automotive, electric, defense, and oil and gas organizations across the U.S., Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Europe. Dragos classifies it as an ICS Kill Chain Stage 2 adversary - meaning it has moved well beyond opportunistic scanning into deliberate operational mapping.

Pyroxene specializes in cross-domain access - bridging IT and OT networks through supply chain exploitation, trusted relationship abuse, and social engineering (including fake aerospace recruiter profiles). Active since at least 2023, it has expanded from the Middle East into North America and Western Europe, targeting manufacturing, aviation, transportation, and utilities. Dragos assesses with moderate confidence that Pyroxene is actively positioning for future ICS-impacting operations.

At a glance:

|

Group |

Origin |

Targets |

Method |

|

Sylvanite |

China-linked |

Electric, oil & gas, water, manufacturing (N. America, Europe, Asia-Pacific) |

Rapid n-day exploitation; enables Voltzite access to critical infrastructure |

|

Azurite |

China-linked |

Manufacturing, defense, automotive, electric, oil & gas (US, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Europe) |

OT data exfiltration (PLC configs, HMI data, network diagrams); persistent access |

|

Pyroxene |

Iran-linked |

Aviation, utilities, manufacturing, defense (US, Europe, Middle East) |

Supply chain exploitation; IT-to-OT pivot; social engineering |

Alongside these new entrants, established groups are expanding their reach. Kamacite, a Russia-linked group, has extended targeting beyond Ukraine, actively scanning U.S. industrial devices including HMIs, gateways, meters, and variable-frequency drives. Electrum, responsible for past disruptive attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure, has now turned toward Poland’s power grid.

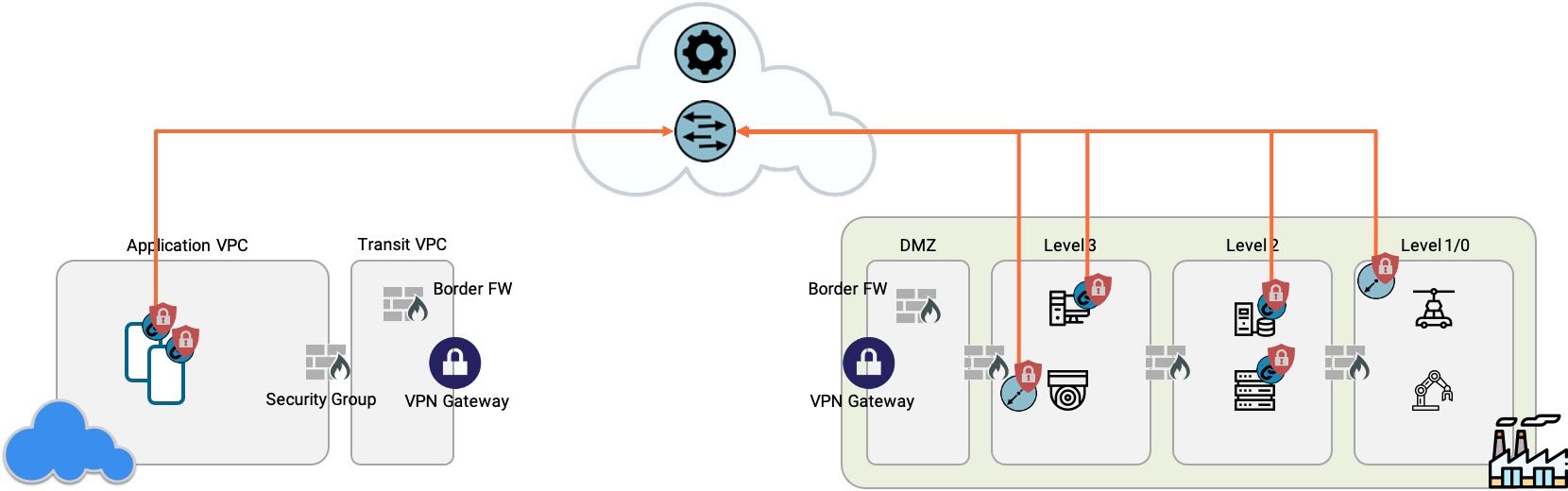

The OT Network Architecture Problem That Makes All of This Worse

What Dragos documents is not simply a volume increase in threats - it’s adversaries moving from reconnaissance to control loop mapping, from access to operational understanding. As Dragos CEO Robert Lee noted in the report, threat groups are increasingly collecting data specifically positioned for future disruption: OT network topology, PLC configurations, alarm thresholds. The intelligence-gathering phase is a precursor, not an end goal.

This matters architecturally because most OT environments were built for reliability, not security. They run Modbus, DNP3, and Profibus - protocols without native authentication or encryption. They depend on legacy systems that cannot be patched or rebooted without halting production. And Dragos’ own penetration test findings year after year reveal the same gap: organizations believe they have IT/OT network segmentation, but hidden connections routinely bridge the two environments.

Traditional defenses share a common set of failure modes in OT environments:

- Perimeter firewalls enforce rules at the boundary but do nothing to stop lateral movement once an attacker gains a foothold inside the OT network - which happens regularly through supply chain compromises, engineer laptops, or remote access portals.

- Network segmentation requires topology redesign and causes operational disruption in environments where uptime is non-negotiable.

- Agent-based security solutions don’t work on legacy PLCs and SCADA systems that cannot run third-party software.

- Ransomware events that appear to be IT incidents are frequently misclassified: many affected systems run Windows but function as SCADA servers or engineering workstations within active control loops, per Dragos incident response data.

What a Defensible OT Network Architecture Looks Like

You cannot install agents on a PLC. You cannot reboot a 1995-era SCADA controller to apply a patch without halting production. The security architecture has to adapt to the operational environment, not the other way around.

An overlay Zero Trust model - one that wraps security around applications and devices without requiring OT network redesign or endpoint agents - addresses this constraint directly. Virtual Chambers create application-scale security perimeters around critical assets: a historian server, a control loop, a group of PLCs. Access is authenticated and authorized before traffic reaches the device. Lateral movement is blocked structurally, not by policy rules that can be bypassed once an attacker is inside the OT network. Legacy industrial protocols get end-to-end encryption without protocol translation or modification.

The agentless approach isn’t a convenience feature - it’s a requirement in OT environments where deterministic control logic cannot be interrupted by software conflicts, crashes, or update cycles. An industrial-rated fail-open bypass ensures production continuity even if the security layer itself is disrupted.

Dragos’ 2025 findings show adversaries are now mapping control loops at granular levels, lowering the barrier to real-world operational impact. That’s a specific, documented shift in adversary capability and intent. The organizations that remain on traditional perimeter models are betting that attackers who already have OT network diagrams and PLC configurations won’t know what to do with them.

That’s not a reasonable bet anymore.

Source: Dragos 9th Annual Year in Review OT/ICS Cybersecurity Report (2026)